IN the last year of his life, F. Scott Fitzgerald sold a mere 40 copies of his books and collected a trifling royalty payment of $13.13.

The Jazz Age genius, who had once been the darling of the literary world with his debut novel, ‘This Side of Paradise,’ died in 1940, believing his legacy was tarnished and his works would not outlive him.

Yet less than a decade later, the world began to reacquaint itself with the writings of Fitzgerald, particularly ‘The Great Gatsby.' Today, his books are studied in school and have sold tens of millions of copies.

In death, Fitzgerald found the fame and acclaim that eluded him in his later years.

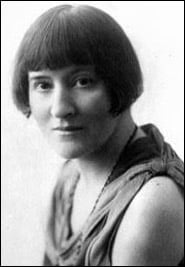

The American author’s story is the polar opposite of Abergavenny’s Ethel Lina White.

During her lifetime, White was a heavyweight in the crime, mystery, and suspense genre and throughout the 1930s equal in reputation to such celebrated wordsmiths as Agatha Christie.

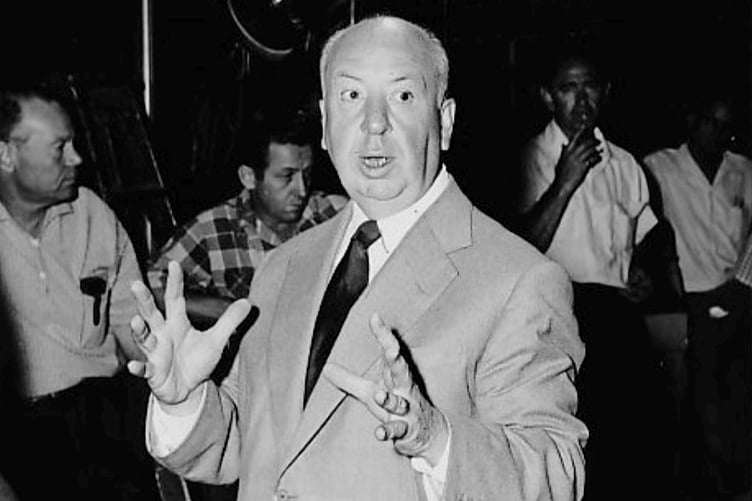

During a hugely successful career, she wrote 17 novels and more than 100 short stories. Her 1936 book “The Wheel Spins” was adapted by Alfred Hitchcock into the movie “The Lady Vanishes.”

Which is quite apt, considering that after her death in 1944 at the age of 68, White slowly disappeared from view, and her books went off the radar for all but the most dedicated ardent of suspense fiction.

The lady who once said, “I never intended to write,” had simply vanished.

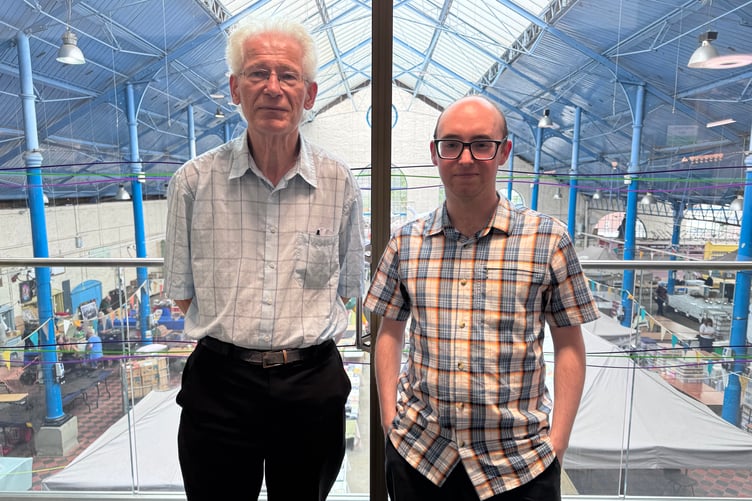

However, thanks to the work of Abergavenny Local History Society and Barnsley man Alex Csurko, who is busy putting the finishing touches to his PhD on the life and works of Ethel Lina White, the crime queen is at long last slowly beginning to appear again.

She may not enjoy an F. Scott Fitzgerald-sized resurgence, but any recognition would be welcome by her growing army of fans.

“During her lifetime Ethel was always quite adverse to any form of publicity and I don’t think that helped with her posthumous reputation,” explained Alex Csurko, who has reluctantly accepted the title of being the world’s leading authority on White, because there is simply no-one else studying and writing about the Greta Garbo of letters with the same degree of obsessive interest.

His enthusiasm for the Abergavenny author and determination to reestablish her rightful rank in the pantheon of novelists is evident.

Alex, who travelled from the north to give a talk at Abergavenny library last week, explained, “There’s so little known about Ethel because she was such a private figure. She even had a habit of putting out false information to throw interested parties off the scent.

“In fact, in a rare interview, she even once went as far as to say, “I was not born. I have never been educated and have no tastes or hobbies. This is my story, and I’m sticking to it.”

As statements go, it does paper to capture a somewhat reclusive and obsessively private mindset. However, the facts remain.

What we do know is that Ethel came from a large family with an abundance of brothers and sisters.

She was born in a house in Frogmore Street on April 2, 1876, the sixth child of William White and his second daughter from his marriage to Eliza Charlotte.

William had been married before to one Emma Bruton. The couple had lived on Merthyr Road until her death in 1871. William married Eliza the following year, and they moved into a terrace on Frogmore Street, which is now marked with a blue plaque.

A builder by trade, William built Frogmore Street house himself, but he would go on to build an abode far grander that would also showcase the brick that he invented.

The Hygeia Rock would make the White family rich. William designed it with the sole purpose of soundproofing and damp-proofing buildings. It worked a treat.

Large quantities of the bitumastic substance were used to build the London Underground, and William used it to great effect in his Abergavenny home, whose unique and somewhat gothic appearance still boasts the sort of majestic and imposing presence only certain houses can.

Nestled in the aptly named White’s Close at the end of Belmont Road, Fairlea Grange looks on an overcast and stomry day like the sort of house Edgar Allen Poe could be found musing about ravens in.

Tucked away in a sleepy corner of Abergavenny, the house where Ethel Lina White spent her formative years remains, by and large, untouched by the modern world.

On a summer’s day when the sky is blue and the sun is high, you can almost hear the ghosts of old gramophones playing their haunting songs, the tinkle of ice cubes in gin and tonics as a lawn party gathers pace, and the click clack of a lonely typewriter as a young girl imagines entire worlds into being.

Although Ethel didn’t write any of her novels here, it’s where the reading and writing bug took hold, and she began to master her craft.

All we know about White’s literary influences from her own tongue is a letter reflecting on her “jolly childhood” and “the Welsh nursemaids whose lurid stories were probably excellent training for a future thriller writer.”

She also said, “I was brought up with Little Women, Melbourne House, and a bound copy of Harper’s Young People.”

As Alex points out, “She was extremely well read and her novels reference everything from Dante to Lewis Carroll, and she really does know how to take a reference and tweak it to her own advantage in her novels.”

Fairlea’s literary-themed interior, such as the fireplace tiles depicting scenes from Walter Scott and Charles Kingsley novels, remains pretty much unchanged. The house was a huge influence on White and inspired some of the locations in her novels.

As did the town of Abergavenny itself.

During his talk, Alex Csurko pointed to the fact that an excerpt from 1929’s “Twill Soon Be Dark” reads, “As usual, he crossed to look through the railings which surmounted a stone coping, to where, in the angle of two walls, he could see the gleam of imprisoned water. A feeder from the river ran under the town, coming to the surface at Market Street,” is pretty much a direct reference to the Cibi Brook running through the Brewery Yard.

In the same book, another passage reads, “From George Street, an alley led down to the meadows which bordered the river.”

As Alex points out, “Although I’ve read the books, I’m not familiar with the history and geography of the town like someone born and bred here would be. So I imagine a local would pick up a lot more Abergavenny references in her work.”

Although in 1884 the Abergavenny Chronicle reported that Fairlea caught fire, no members of the White family were injured.

There is a long-held rumour that William lost and gambled away Fairlea during a card game with the owner of The London Public House, which used to stand on Monk Street. However, considering the family lived there long after William died in 1901, it seems as fictional as one of his daughter’s creations.

Upon the death of her mother in 1917, the family house and business were sold, and Ethel, who by this point had only a handful of short stories published, moved to London with her two younger sisters - Annis and Marjorie.

Alongside continuing to write short stories, Ethel found work as a clerk in the Ministry of Pensions. She didn’t like it, and in 1919, after being offered ten pounds to write a short story, she threw away the promise of a safe job and would later write, “I couldn’t stand office life, because of the lack of fresh air.”

For the next eight years, she would continue to etch out a living writing short stories for magazines and really perfect her writing style.

In 1927, everything changed when Ward Lock & Co. published her first novel, a romance entitled “The Wish-Bone.” Ethel was 51.

The gates of the dam had been opened, and the novels began to flow like a torrent. In 1931, she published her first thriller, “Put Out The Light,” followed by “Fear Stalks The Village,” and things began to gather steam.

Although extremely prolific, particularly for an author who began penning novels so late in life, White would often profess amazement that she managed to put pen to paper, let alone orchestrate complex plots.

She explained in a letter to her publisher, “My method of working is so weird that it is a mystery to me that there really is a novel to show for it.

During a normal writing day, Ethel explained that, “I begin about 12, with writing materials, write a few lines, then get a glass of water - another line or so - smoke a cigarette - another line - play with the kitten - and then break for a cup of tea. But somehow, a book does get written.”

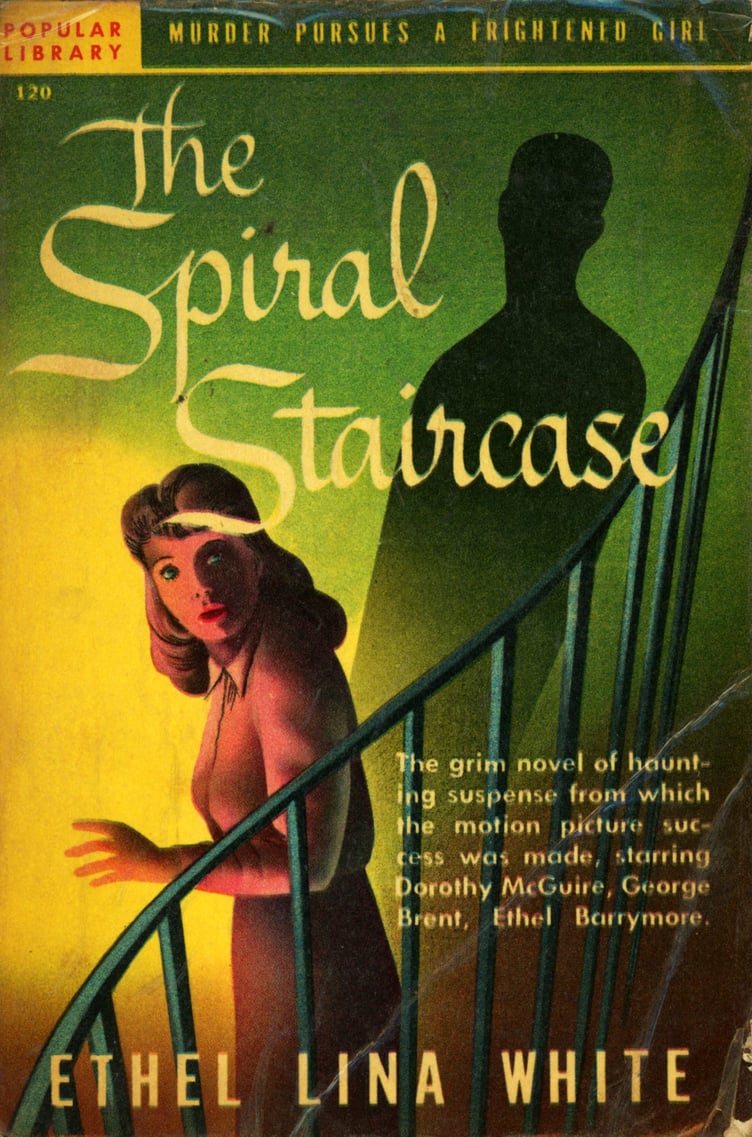

“Some Must Watch,” published in 1933, was later adapted as the film “The Spiral Staircase,” and in 1936 came the big one, “The Wheel Spins,” which in 1938 Alfred Hitchcock turned into the movie “The Lady Vanishes.”

Interestingly, it was the Hitchcock connection that led Alex Csurko to a five-year study of Ethel Lina White.

He explained that during his undergraduate studies on the great director, he was introduced to ”The Lady Vanishes,” and this led him to do a PhD on the author.

Although overlooked compared with others who wrote in the same genre, Alex believes that White was a true innovator and deserves to be recognised as such.

He explained, “She took a style in its infancy and added so many threads of classical literature to it. For example, her first detective novel, Put Out The Light, is a direct reference to Othello.”

Although there may a distinct lack of biographical information on the life of Ethel Lina White, as the writer Irvine Welsh recently wrote in The Guardian, "Novels, no matter how well researched, composed or projected, are always - whether you like it or not - at least tangentially about you."

So if you want to know more about the lady who vanished, read her books. It's all there in black and white. A life and its secrets laid bare in psychology, plot, theme, and narrative.

In February 1939, White returned to her old town during a packed showing of “The Lady Vanishes” at the Abergavenny Coliseum.

White was a huge fan of the cinema and once remarked, “To my mind, it is a perfect form of mental release. I used to go before it was general and people sneered at me for my base taste, but I used to love the unfamiliar American backgrounds.”

After being invited onstage by Mayor W. Rosser, she was congratulated on her success. To which she modestly replied, she was only invited because, “I do not take up much room.”

“The Wheel Spins” would cast a long shadow over the rest of White’s career. It made her famous, but it would also be the yardstick by which future thrillers such as “The Elephant Never Forgets” and “The Third Eye,” whose rights were sold to Universal, would be judged.

Five years after she returned to her hometown as a world-famous writer, White would be stricken with ovarian cancer. She died on August 13, 1944, aged 68.

Her last will and testament saw her leave all her worldly belongings to her younger sister Annis, along with a macabre request that, “I give and bequeath unto Annis Dora White all that I possess on condition she pays a qualified surgeon to plunge a knife into my heart after death.”

Some have suggested that such a strange missive betrays White’s longstanding fear of being buried alive. Others, that is, is simply one last example of her dark humour.

Like so much about the author, the truth of the matter will remain unknown. And that’s perhaps how the lady who specialised in psychological thrillers and mystery would have liked it.

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.