The past few years have witnessed a relentless barrage of devastating floods across the globe and this is a direct consequence of climate change, which is altering weather patterns and making such events more frequent and severe As global temperature continues to rise we can expect even more intense and frequent floods in the future, because warmer air can hold more moisture.

Recently in Monmouthshire we have experienced flooding in several places, including Abergavenny, Monmouth and Skenfrith and these were caused by the storm which was given the name Claudia. Five years ago we were hit by Storm Dennis and in 2024 it was storm Bert. This year the River Monnow reached record levels and the amount of rain which came very fast in a short space of time was unprecedented. Obviously we need to take a new look at our flood defences for matters can only get worse.

I well remember visiting Lynmouth in Devon as a child after it was flooded in 1952. Intense rainfall flooded Exmoor and then poured into this small village, completely destroying more than 100 properties and drowning 34 residents. At that time, It was the worst river flood in English history.

The 1607 flood in the Bristol Channel and Severn Estuary was the worst natural disaster ever recorded in the British Isles. It affected most of the South Wales coast from Carmarthenshire in the west and to Monmouthshire in the east and there were a large number of fatalities.

Over the passing centuries these sea defences have been re-shaped, restored and improved many times, but a period of neglect led to a great flood when wind and sea conditions combined to bring the waters of the Severn roaring overland, creating havoc on both sides of the estuary.

In those pre-newspaper days, only the most notable events went on record, and a broadsheet was published giving a detailed account of this disaster: ‘About nine of the clock in the morning, the same being most fairly and brightly spread, many of the inhabitants prepared themselves to their affairs. Then they might see afar off huge and mighty hills of water tumbling over one another as if the greatest mountains in the world had overwhelmed the low villages and marshy grounds. Sometimes it dazzled many of the spectators that they imagined it had been some fog or mist coming with great swiftness towards them, and with such a smoke as if mountains were all on fire, and to the view of some it seems as if millions of thousands of arrows had been shot forth all at one time. So violent and swift were the outrageous waves that less than five hours space most part of those counties (especially the places that lay low) were all overflown, and many hundreds of people, men, women and children, were quite devoured; nay, more, the farmers and husbandmen and shepherds might behold their goodly flocks swimming upon the waters – dead.’

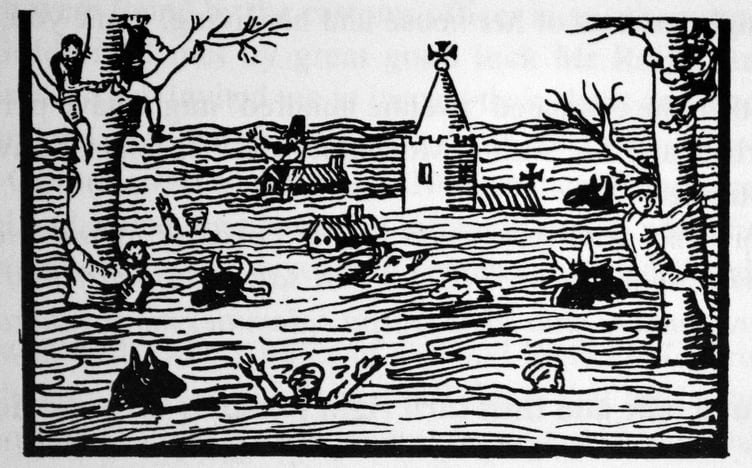

A contemporary woodcut shows a church steeple rising from the flood waters, two cottages and two trees, one of which holds a man and boy. Animals are swimming in the water and people climbing both trees to escape the drowning. A man wearing his tall steeple hat sits on a roof; animals and human beings swim in the water. This is all rather quaint but fails to depict the sheer misery and horror of the occasion.

The flood happened at full moon, when tides are at their highest and the entire moorland between Cardiff and Portskewett was flooded. The population of the moors at that time was much higher than it is now. Descriptions of the disaster claimed that the number of people drowned was at least 2,000, ‘and all wild beasts and vermin tried to escape from the water by getting to the most elevated banks and parts of the land.’

We are told that 26 parishes in Monmouthshire were ruined, and these included: ‘Mathern, Portescuet, Caldicot, Undy, Rogiet, Llanfihangell, Ifton, Magor, Redwicke, Gouldenlifte, Nashe, Saint Pierre, Lanckstone, Wiston, Lanwerne, Milton, Saint Brides, Peterston, Saint Mellins, Romney, Marshfield and Wilfrick.’

The flood affected an area some twenty-four miles long and about four miles wide and the damage to property was thought to be near £100,000. Many people perished from starvation and extreme cold. But the death toll could have risen higher if Lord Herbert had not sent out boats delivering meat and other necessities to flooded homes.

Despite a fairly recent suggestion that the flood was the result of a tsunami, research has now confirmed that the cause was a major storm surge created by persistent gale force winds and low air pressures coupled with an exceptionally high tide. The known tide height and coastal flooding elsewhere in the British Isles on the same day all point to the cause being a storm surge rather than a tsnami. The Spring tide in the Bristol Channel on 30 January 1606 reached a height of 25 feet and this occurred in combination with a severe south westerly gale.

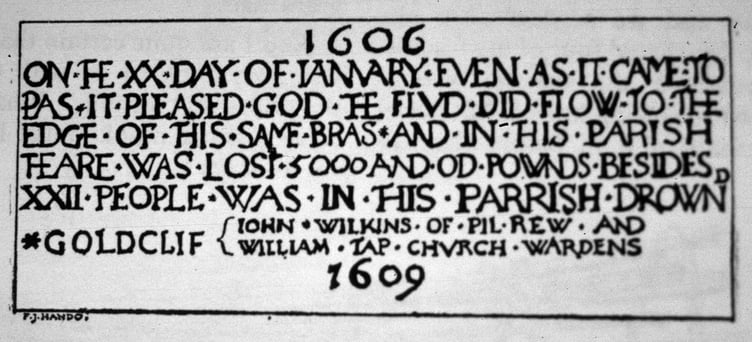

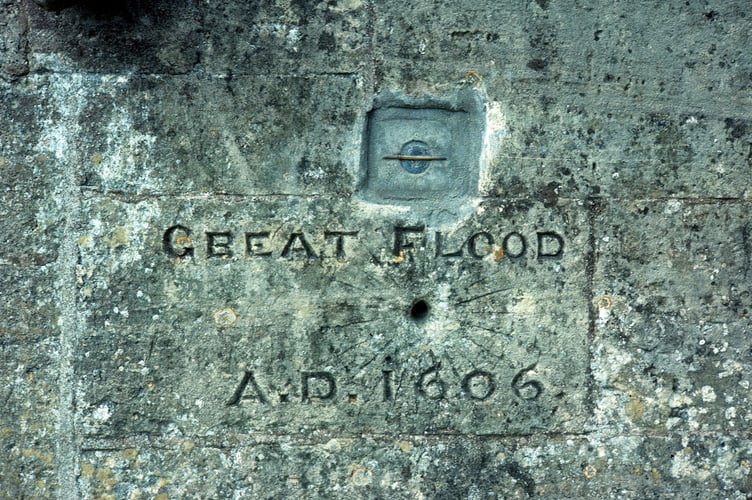

Two miles from the sea, a brass plaque inside the church of St Mary Magadalene at Goldcliff, on the north wall near the altar, and about 3 feet above ground level marks the height of the flood waters. It records the year as 1606 because, under the Julian calendar in use at that time the new year did not start until Lady Day, 25 March

A stone in the chancel of Peterstone church also marks the level to which the water rose. The church is now privately owned, so this inscription can no longer be visited. In recent years a vertical stone has been erected near Peterstone Village Hall, bearing a mark that indicates the level reached by the flood water. Redwick Church has a strip of brass set into the wall near its entrance, 4ft 10ins above ground indicating the water’s highest point. At Nash Church, five feet up one of the tower buttresses is a deep slot marking the height of the flood.

Before the moorland areas that border the Severn Estuary on the Monmouthshire coastline were reclaimed from the sea, they must have resembled a vast lagoon. It was the Romans who first realised the potential of this land and they constructed a strong rampart some twenty miles in length, stretching from Sudbrook to the mouth of the Usk and from there to the River Rhymney. The moors were drained by a complex system of reens and ditches in order to make the land suitable for growing wheat and grazing animals

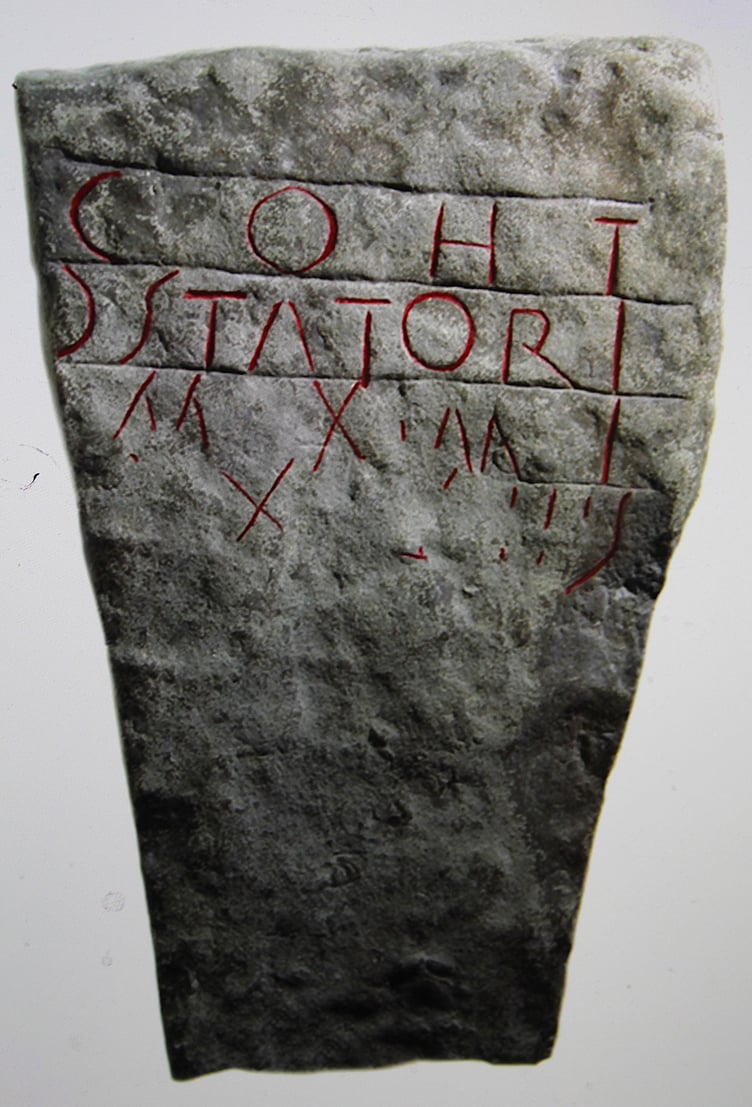

In 1878 an inscribed stone was found beside the sea wall at Goldcliff, stating that a cohort of the centurion Statorius had built two miles of the wall built to reclaim the vast tract of the Saltings, the alluvial deposit of the Severn, which now forms the rich Caldicot and Wentloog Levels. This inscribed stone can be seen in the Roman Museum at Caerleon and it is thought to date from the 2nd or early 3rd century.

.jpeg?width=209&height=140&crop=209:145,smart&quality=75)

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.