IN Victorian times being committed to a “lunatic asylum” was considered a fate worse than prison. These forsaken outposts of ennui and despair were the last place any mentally unwell person would want to end up if they were to have more than a snowball’s chance in hell of getting fighting fit again.

There was more horror than healing to be found behind the imposing doors of these guarded buildings which became all the rage under the reign of the Widow of Windsor - Queen Victoria. In short, no matter how accommodating their regime, they were prisons disguised as hospitals. Patients were not treated like people who needed help, but more like dangerous wild-eyed beasts whom the public needed protecting from, less their lunacy infected the greater good like a particularly potent parasite.

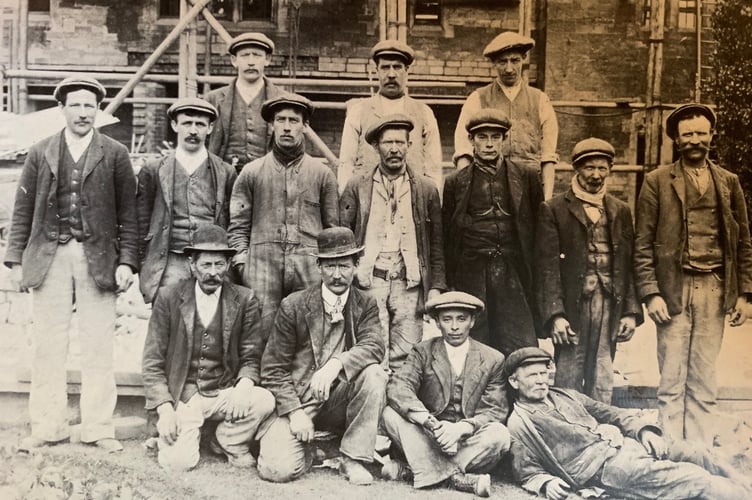

Originally known as the Joint Counties Lunatic Asylum, and later the Monmouthshire Mental Hospital, the sprawling Tudor Gothic-style institution which overlooked and cast a shadow over Abergavenny for well over a century was erected in 1851 and named Pen-y-Fal. Originally intended to house a maximum of 210 patients, the hospital was catering for well over twice that number by 1867 and subsequent extensions to the main hospital entailed that eventually Pen-y-Fal housed a staggering 1,170 inmates and covered 24 acres of ground.

In its early days, postnatal depression, alcoholism, senile dementia, or even infidelity, which was then classed as ‘moral insanity,’ were grounds enough to have you committed indefinitely to its grim environs.

Many a black sheep or rebellious outsider was condemned to the care of the asylum under the label of being prone to anti-social behaviour or melancholia. All the authorities needed was a doctor’s certificate and a relative’s signed agreement that you were in desperate need of special measures and away with the men in white coats you would go. In fact, ‘gone to Abergavenny’ used to be a metaphor in the South Wales valleys for going insane.

Men of wealth often used the asylums to ditch unruly wives and give them a short, sharp shock. They would take advantage of the medical condition known as ‘hysteria’ to rid themselves of ladies who didn’t act as polite and agreeable as the gentleman thought was proper.

Overall, the chances of admission were higher if you were a woman from any social class. Distraught mothers who lost their sons or husbands to war, those classed as leading an ‘immoral life,’ having ‘domestic trouble’ having ‘menstrual problems,’ or prone to ‘menopause’ or ‘nymphomania’ could all be classed as being in dire need of being ‘mentally corrected’. Worst of all, women who thought for themselves and wanted to educate themselves further were classed as having “over-action of the mind.” In certain asylums ‘book reading’ was listed as a reason for admission.

For curiosity’s sake and to poignantly prove how much more enlightened we are as a society regarding the complexity and maladies of the human condition, here are just a few of the actual reasons cited for admission to asylums such as Pen-y-Fal between 1864 and 1889.

Intemperance and business trouble, being kicked in the head by a horse, imaginary female trouble, hereditary predisposition, jealousy and religion, laziness, masturbation for 30 years, mental excitement, opium habit, over-action of the mind, over-study of religion, overtaxing mental powers, political excitement, religious enthusiasm, asthma, bad company, bad whiskey, dissolute habits, egotism, epileptic fits, time of life, superstition, spinal irritation, grief, feebleness of intellect, gathering in the head and dissipation of nerves.

The list goes on, much like a historic testament to the twin evils of ignorance and prejudice, but to break it down to its bare bones, madhouses were dumping grounds for the poor, unsightly, and down-on-their-luck members of society, including many children with epilepsy and developmental disabilities that the public at large wanted to be removed from their collective sight.

In the case of many of the inmates, their very difference and habit of walking a different path and marching to the beat of a different drum was the very reason the status quo felt the need to steamroll them into meek submission by any means necessary. And as you can see from the ludicrous reasons for many of the admissions, the means were often foul and completely unnecessary.

Once you were safely under lock and key there was no official release date. In fact, you couldn’t even appeal against your detention. Your best hope would be a kind friend or relative who was in good standing in society would request you be discharged. Until that distant, and for some, impossible dawn, life was a bland, crushing and drawn-out affair capable of eroding the soul and paralyzing the mind.

Privacy was not considered essential for a patient's well-being. The pauper wards were filled with as many beds as humanly possible, all lined up in regimented rows with no consideration for personal space. Males and females were strictly segregated and the day revolved around a tedious routine of waking, eating, and working. For men, this involved helping out on a nearby farm or hospital bakery, and for women, the hospital laundry. Both genders were expected to pitch in with cleaning duties. For those deemed unfit or unwilling to work, they would be allowed to roam the grounds for an hour every morning or afternoon. Men were often encouraged to participate in gardening or sporting activities but the fairer sex was denied to partake in such demanding pastimes and had to remain content with a leisurely stroll around the grounds instead.

By far the worst aspect of asylum life was the experiment and barbaric treatments patients were subjected to in the name of progress and endeavor but which amounted to torture by another name.

Regarding mental health issues, the keywords, particularly in Victorian times, were containment, suppression, and restraint. If a patient stepped out of line there were a number of ways to reign them in. Straight jackets and padded cells were a popular way to stop patients from harming themselves and others. Fastening excitable and aggressive patients to their beds was also a routine method to curb the ‘craziness’.

Those prone to melancholy received hot baths in a bid to lift their spirits. Such a treatment sounds warm-hearted and progressive but really it was ignorance dressed up as science. The patient had no choice in the matter. They were placed in the tub with water up to their chin. They were then covered with a canvas sheet, with a little hole for their head and they were then left to stew in their own juices for hours, in some cases days, as cold water was drained from the bottom and a ready supply of warm water was constantly added.

Yet such a water treatment seems almost leisurely compared with its cold-water counterpart. If you were deemed in need of ‘calming down’ by the medical authorities, there was a range of options at their disposal. In some asylums, a patient would be forced into a cold shower room, restrained, and doused until compliant. In others, an individual would face the humiliation of being tied naked to a chair as bucket after bucket of ice water would be poured over their helpless heads. And here’s where it gets particularly medieval. Some asylums adopted a system similar to the ducking systems once used by religious and perverse zealots during the witch hunts. Patients would be strapped to a chair and repeatedly dipped into small ponds until they were on the brink of passing out.

They were then given a few minutes to regain their senses before the whole process began anew and the patient was satisfactorily broken.

Water treatments could carry on for days and would only end when an asylum physician had deemed that the individual’s state of mind had been put at ease and behaviour modified.

The art of spinning was a particularly torturous treatment. Patients were strapped to a large wheel and spun at high speeds. Except for making them puke profusely, it’s not certain what desired effects a spin on the wheel was supposed to invoke. Even more sinister and barbaric was the branding iron. Like it said on the tin, hot irons were pressed against a patient's naked flesh in an attempt to ‘bring them to their senses.’

Using drugs to treat asylum patients wasn’t widespread in Victorian times but towards the end of the nineteenth century, a chemical cosh called Paraldehyde became all the rage. The sedative had a range of uses from inducing sleep to calming convulsions and nullifying fits of rage. Patients would often have their evening tea spiked with this reliable downer.

As the twentieth century dawned, the older and more primitive ‘treatments’ were discarded in light of what were considered more progressive treatments such as lobotomies and ECT (Electroconvulsive therapy).

One psychiatrist described lobotomy as “putting in a brain needle and stirring the works.” Working with the sort of ice picks and restraints that wouldn’t look out of place in a medieval dungeon, early practitioners of this perverse practice appeared to believe they were like scientific exorcists, drilling holes into skulls to release evil spirits. In reality, they were gleeful butcherers who were working blind to mangle and maul, that most intricate, delicate, and wonderous thing - the human brain.

By forcing an 8cm steel spike attached to a wooden handle through a hole drilled in the skull, surgeons would literally stab and slash at the brain to sever any connection the frontal lobes had to the rest of the brain. The results were hailed as a miracle cure and a magical fix. The men in white coats declared that in patients where there was once rage, there was now calm, where once there was turmoil there was now tranquility, where once there were the demons of delirium and disturbance there were now the angels of acceptance and acquiescence. Such was the fervor to promote this revolutionary treatment, that at its peak the UK was conducting 1,000 lobotomies a year.

In 1949 Egas Moniz was awarded the Nobel Prize for introducing lobotomy to the world. Yet by the mid-1950s, the procedure had fallen from grace.

The mute indifference, robotic automation, and gross retardation of many who had survived the intrusive workings of the lobotomy spike haunted those who once believed that hacking away at the brain could offer up any sort of redemptive epiphany. It did not. All it did was lead to the terrible ruination of human beings.

Take the case of John F. Kennedy’s sister, Rosemary. In 1941 she was involuntarily committed to an asylum by her father for mood swings and what was classed as ‘challenging behavior’. At his request and without her consent she was subjected to a lobotomy. The aftermath was horrific. Rosemary couldn’t walk or talk and suffered from permanent incontinence. Her intellectual capacities were that of a two-year-old child. She had been failed by both science and society.

Yet the tide was turning and the darkness slowly began to recede as a new approach and understanding took hold. Antidepressants and antipsychotics coupled with a determination to understand, helped shine a light on that which had been previously condemned and left to rot in the shadows. From the 1980s onwards the haunting and historic asylums began to shut up shop and in an ironic twist of fate, care was given to a community that had previously exiled anything different or difficult.

Pen-y-Fal finally closed its doors for the last time on August 17, 1996, and a large part of the original building still stands as part of a sprawling housing development that is riddled with an abundance of clues and pointers as to the former legacy of the site. Not least the innocuous and pleasant grassy verge where today children play and dogs walk, and beneath, three thousand poor souls are buried in unmarked graves.

Their tales may be forgotten but the story of their lives remains a valuable lesson to us all.

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.