IT is not widely known that while one out of every 20 British prisoners died in Nazi POW camps in Europe, in Japanese camps the figure was one out of every three, not including those who died soon after from ill health.

This stark difference is partly due to tropical diseases, but was mainly the result of harsher treatment rooted in the Japanese military’s contempt for the prisoners.

According to the warrior code of the samurai, the POWs should have died in battle or committed suicide instead of surrendering, although it's interesting to note that, contrary to popular belief, relatively few Japanese actually lived up to this ideal themselves.

Decades later, the son of a World War II veteran—who survived three years in the infamous Japanese-run Kinkaseki POW camp in Taiwan—returned to the site and described the journey as “the most emotional thing I’ve ever done.”

When Peter Bowkett made the trip to Taiwan to visit the soil where his father, Harold Bowkett, and many other brave men sweated, bled, cried, and died upon, the experience was life-changing.

Peter recalled, “When I was a young boy of seven or eight years of age, I remember asking dad why he had scars on his back, and he told me that they were from working in the copper mine whilst he was being held at a Japanese POW camp in Kinkaseki - Formosa (Now Taiwan).

“Growing up, I became more and more aware of the fact that he had been a FEPOW (Far East Prisoner of War) as many of his friends were FEPOWs, and they would meet up on a regular basis with their families.

“He proudly had a FEPOW badge on the front of every car he owned, and many times when he returned from a big annual meeting in London or Blackpool, he would often tell us about someone he met whom he hadn’t seen since the end of the war.

“Throughout my childhood, the name ‘Kinkaseki’ was never far from my mind, but apart from a few funny stories, Dad never talked about his times as a POW, but I was aware through the people I met over the years, the strength of the friendships and camaraderie built up between them all.

“After dad died in 1990 I read a little more about Kinkaseki. Tony, my brother, lent me Jack Edward’s famous book ‘Banzai you Bastards’. Jack had inscribed Dad’s copy of the book along the lines of - ‘To Harold - this book is as much about your story as mine.’”

In the wake of the British capitulation at Singapore, which Winston Churchill called the worst disaster in British history, Harold Bowkett, Jack Edwards, and their comrades were herded into a rusty old transport ship taken to Kinkaseki and put to work in the copper mines.

In his book, which took him over 40 years to write because he was ‘too traumatised by the experience,’ of trying to put his memories down on paper, Edwards describes the first day in the mines as a ‘descent into hell.’

Captives at Kinkaseki spent their days in slave labour, digging upwards into a copper seam in sulphur-polluted water in conditions where there was the constant danger of a cave-in.

Starvation, brutal beatings, and sadistic forms of torture were commonplace, as were the killings of POWs for minor infringements. In some cases, prisoners were butchered to simply appease the sick and twisted desires of crack despots who, without mercy and unchecked by morality, ended life on a whim, as the craven and ungodly greed for power made monsters of men and monuments to murder.

Peter Bowkett explained, “During his time in the POW camps, although dad was starved, beaten and tortured, he pretty much compartmentalised that chapter in his life.”

Peter made contact via email with Michael Hurst, who lives in Taiwan and perpetuates the memory of the FEPOWs on the island. Michael told Peter that they hold an annual remembrance service in Taiwan, and with his wife Liz’s support, Peter decided to sign up for the November 2009 trip.

Peter explained, “Although my dad was a great pacifist, he always hated the Japanese for obvious reasons and had he lived, I don’t believe he would have ever wanted to return to the site of his past imprisonment, but it is something I felt I needed to do.”

“

My mother always said my father was a different person after he returned from the war

Frank Williams

Meeting up with Michael Hurst at the Taiwan airport, Peter discovered there were 26 people in their party, including six FEPOWs who had been in the camp at Kinkaseki.

Peter said, “Three of the FEPOWs had been back before, and for the other three, it was their first visit. One of them had a Welsh accent, and I later discovered it was Newport man George Reynolds who had attended dad’s funeral in 1990.

“The FEPOWs confirmed the conditions they were kept in - tortured, beaten, made to walk to the mines to work, and starved - some were less than five stone in weight when freed.

“They had to steal food from anywhere they could and would eat grass, leaves, insects - anything to try and keep alive.

“Many died in captivity and were buried at the camps - later these bodies would be repatriated to Hong Kong.”

Peter added, “We made two trips to Kinkaseki, and on reflection, I was glad because the visits were very emotional.

“The weather was damp and misty, and George told us that it seemed to rain most of the time they were prisoners there. I found it sad that the surrounding mountains were very similar to those in Clydach, where Dad was raised.

“One 91-year-old FEPOW didn’t think he could face going into the copper mine again, but somehow after all these years, he found the strength to face his demons and did so admirably.

“The next day, we visited the second POW camp - Kukutsu. This was known as the Jungle Camp, and it was where the POWs were sent to die.

“Seeing both these sites, I was now able to link together the actual places with the images I’d had in my mind for many years, and I really did feel a connection.

“My sister Cath best summed it up in a text message that read - ‘What a pity we didn’t know more about all this before Dad died.’

“The fellowship of the people on the trip was amazing, and to meet, spend time with, and listen to the stories of the POWs was something Liz and I will never forget.

“After finally visiting a place I’ve known about for over 50 years but never seen with my own eyes, I personally feel that something has been lifted from my shoulders. In summary, the trip to Taiwan was the most emotional thing I’ve ever done.”

Returning to the local area at the end of the war, Harold Bowkett was given a hero’s welcome, and not long after, he met his wife-to-be, Marie.

“Because of what he had been through, Harold was already a well-known character in the area when I met him not long after the war ended,” revealed Mrs Marie Bowkett.

“It may sound daft, but I fell head over heels in love with Harold when we were first introduced. I was working at the post office, and he was a Post Office Engineer.

“Harold was a great raconteur and told me how, after Kinkseki was liberated by the Americans, they took them to Manila and brought them home via America, which they crossed a lot of by train.

“We married in 1947 and went on to have five children and a wonderful life together. Although he didn’t talk much about his time in the camp, he told me how appalling the conditions were.

“I know he lost a lot of good friends out there, but Harold was a born optimist and a very religious man.

“He told me that some men just gave up and lay down and died. Harold, on the other hand, tried to stay strong and was determined to survive the horrors of Kinkaseki and return to the land that he loved and longed to spend the rest of his days in.”

Welcome To The Jungle

In times of adversity, the human spirit manifests its resilience in many forms. Japanese prisoner-of-war Ronald Williams found the strength to persevere in the face of the brutality and degradation his captors dished out on a daily basis, through verse, artwork, and good old-fashioned British humour.

Royal Artillery officer, Lieutenant Ronald Williams, passed away prematurely in 1969, aged 58, without fulfilling his ambition to publish in book form the papers and camp journals he wrote during his time as a Japanese prisoner-of-war.

On the 60th anniversary of VJ Day, his son, retired hospital consultant Frank Williams, managed to persuade his 95-year-old mother, Margaret Williams, to let him investigate the papers his father wrote about his time as a prisoner on the Japanese-occupied island of Java.

Frank explained, “My father never told many people about his experiences, but in the last six to nine months of his life, he started telling me things about his time as a prisoner. It was as if he had a premonition of sorts that he was going to die and wanted to tell his tale before he did.

“He died from a heart attack, which was in part due to the effects of smoking, but it was also due to the long-term debility he suffered through privation, disease, and malnutrition as a Japanese prisoner-of-war for nearly four years.”

After two years of research, Frank used the copious papers and illustrations his father had created and pieced them together with the recollections he learned first-hand to publish a book for his mother’s 90th birthday called, ‘Under the Poached Egg: Living on the Edge of Reason.’

Frank revealed, “This was to be the original title of my father’s book. The Japanese flag was often referred to for obvious reasons as a ‘poached egg’, and the POWS were the toast for over three and a half years! My father had always wanted to publish the book when he retired, but unfortunately, he never realised his ambition.”

Some time after the book’s publication, Frank found out through the Java Far East POWS 42 Club that copies of his father’s original camp journals were in the archive of the Imperial War Museum.

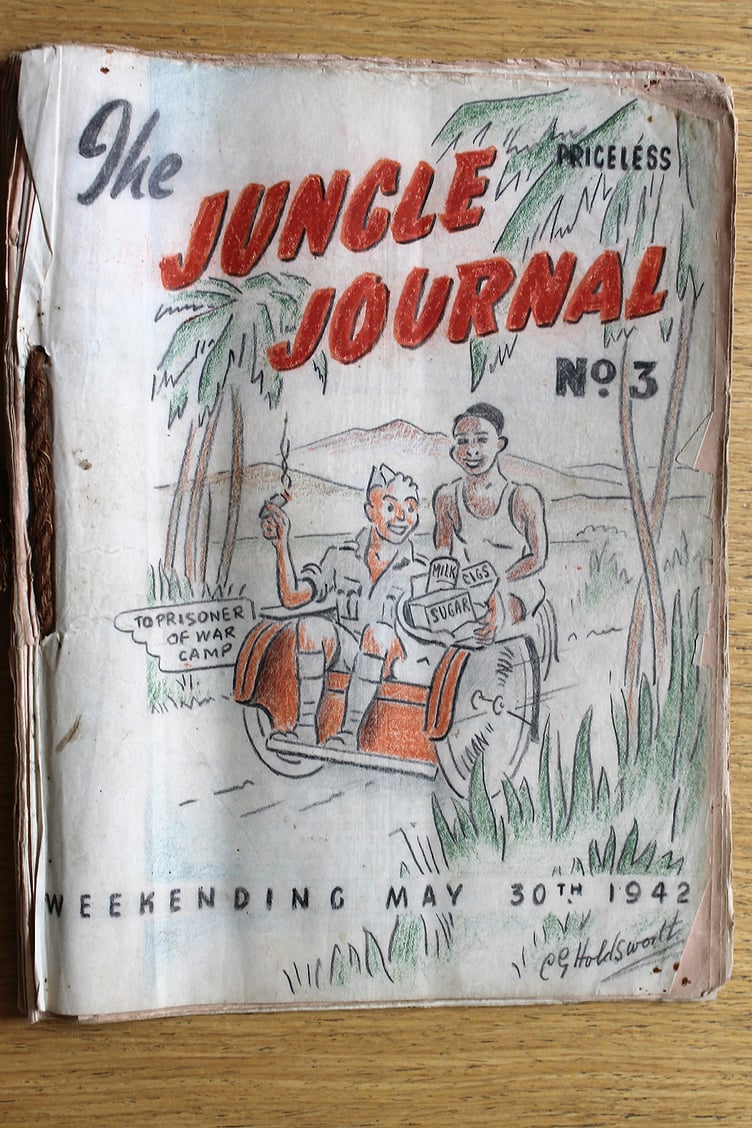

Frank said, “The first journal was ten pages long, but as more prisoners became involved, they went up to 50 pages. The embellished poems and illustrations convey the alternate horrors and banality of POW life and the humour that helped the men survive the beatings, deprivation, and death of comrades. It is remarkable that these journals were produced under the noses of their unsuspecting captors.”

Frank added, “The journals were not only a distraction from the terrible things they were experiencing, but it was a way for them to keep their spirits up and hold onto their sanity.

“The men were very clever and made only cryptic references to the Japanese and used pseudonyms to hide their identities from the camp censor. Yet they understandably detested their captors, and you can definitely sense that undercurrent of fierce hatred running all the way through the journals, yet it is also evident that despite the grim conditions, the men managed to hold onto their humanity.”

Frank explained that his father was deeply demoralised by the lack of a concerted fight by the Allies in the defence of Java, but felt that the unexpected fall of Singapore was the turning point that sealed the island’s fate. Ronald Williams wrote in retrospect that the Japanese were a merciless and determined enemy fighting an ill-equipped and disorganised multinational Allied force, and that most British men would have fought to the bitter end if they had foreseen their ultimate fate.

In a diary entry of March 13, 1942, the Lieutenant writes, “We learned quickly that the Japanese are predictably unpredictable. Japanese counterparts told our senior officers that Allied officers would be treated very well and would never be short of cigars, alcohol, and man servants. What a sick joke that turned out to be.”

Frank revealed, “My mother always said my father was a different person after he returned from the war. She described him as a barely recognisable man with severely cropped hair, yellowish skin, sunken eyes, and dreadful teeth. She said his appearance turned heads in public for several months, and he never recovered the self-esteem he had prior to going to Java.

“He lost a lot of friends in the Far East and went to a few reunions when he came back, but he never really wanted to talk about his experiences as a POW. His was a theatre of the Second World War which has been largely swept under the carpet of recorded military history. Returning Far-East POWs were actively discouraged from talking about their experiences.

“He did, however, write a great deal of poetry whilst in captivity and of course organised the camp journal - The Jungle Journal. However, production was often interrupted by camp guards confiscating pens and paper.”

In 2013, Frank published The Jungle Journal: Prisoners of the Japanese in Java 1942-1945.

Frank explained, “The Jungle Journal is a combination of material from the Imperial War Museum, handwritten material, and a typed manuscript my father was intending to publish. The remainder I have compiled from archival material, newspaper articles, family letters, and other personal accounts.

“No official Allied military records survived the Java campaign, and personal records are sparse. The Japanese burnt all archives of POW camps and often silenced, permanently, any witnesses to their atrocities.

“As such, The Jungle Journals are dedicated to those men and women, from all services and walks of life, and of all nationalities, who maintained their pride with great courage while captives of the Japanese in the Far East, from 1941-1945.”

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.