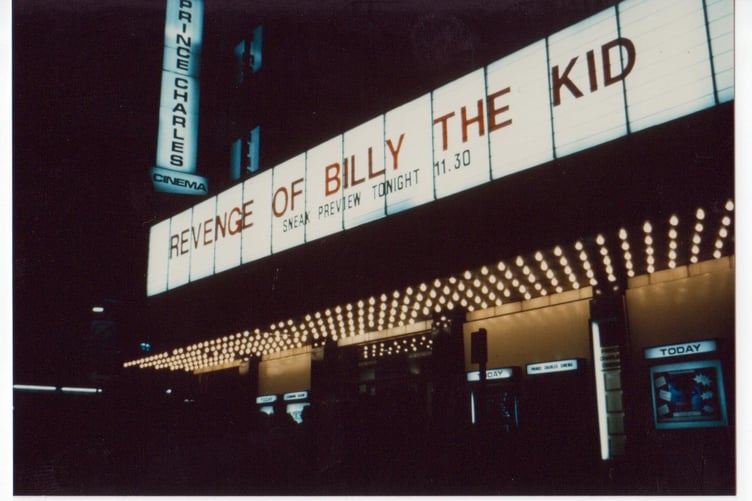

IF you’re a huge fan of Westerns, you might want to give The Revenge of Billy the Kid a miss. The title is a little misleading!

Directed by Jim Groom, it’s less about outlaws, life on the trail, the fastest gun in the West and a vengeful sheriff, and more about a peculiar farming family called the McDonalds.

In particular, it’s about the patriarch of the clan, Gyles McDonald, who unwittingly unleashes seven shades of hell after he enjoys an intimate relationship with a goat.

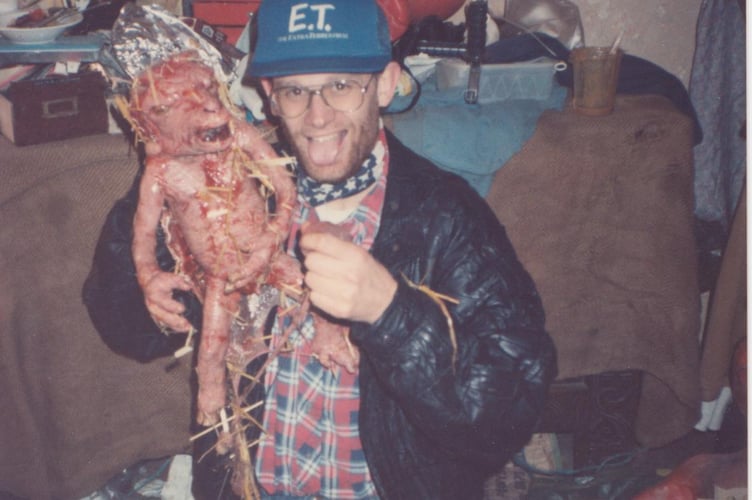

The goat’s offspring is not welcomed with loving arms by the rest of the family, with the exception of his half-sister, Ronnie McDonald, and after its mother’s lover tries to drown it in a sack, it returns, more demonic and demented than anyone could ever imagine, and seeks its terrible revenge.

“What’s all this got to do with Abergavenny?” You might ask!

Well, alongside Mousehole In Cornwall, The Revenge of Billy the Kid was filmed in a farm just on the outskirts of town.

And if you were a teenager growing up in the local area in the early nineties, chances are at some point you might have got your hands on a VHS copy, placed it in the prehistoric piece of tech, pressed play, and murmured “Jesus!”

Love it or hate it, and the movie remains as divisive now as it did then, if The Revenge of Billy the Kid does one thing well, it certainly provokes a reaction.

As scriptwriter Ross Smith told the Chronicle, “Even at its premiere in Cannes, at least half of the audience walked out in disgust in the first ten minutes, but the other half loved it. It’s all about finding your audience.”

Although some reviewers, such as the South Wales Echo, described it as,

“A wicked, extremely funny shocker which contains every bad taste joke in the book.” And the Huddersfield Daily Examiner enthused,“An outrageous comedy with full-blooded vulgarity which had me rolling with laughter. This is one of the funniest and most unusual features in a long time.”

Other reviews were particularly damming. The Video Business Times solemnly announced, “This is a sick film. It will upset a lot of people.” The Daily Mirror branded it “Nauseating!” And one critic writing in the Yorkshire Evening Post at the time barked, “I have always thought I am pretty broadminded and am against any form of censorship but if someone builds a bonfire with copies of this appalling film, I will gladly stand by spraying petrol on the flames.”

Ross mused, “I thought some of the reviews were a bit harsh, but at the same time great, because the whole ethos behind Billy was about sticking up two fingers at the uptight and po-faced British film establishment and making a fun bit of entertainment.”

If they wanted to upset the apple cart, the film definitely did the trick, but in the final analysis it worked a little too well.

As Ross explained, “We thought we were going to get a theatrical release, especially on the back of all that publicity, but our distribution company didn’t want to know, and it went straight to video, which was a bit of a kiss of death in those days. There was no big event, no high-profile reviews, and it sort of fell by the wayside.”

Ross added, “Even though, according to the 1994 BFI Yearbook, the VHS of Billy was rented 68,000 times in its first six months, which made it the fourteenth most-popular European movie of 1992. All of which, I suppose, constitutes a commercial success considering Billy’s budget. Not that any of us ever saw a penny. In fact, the only person who made money from Billy the Kid was an Abergavenny farmer called Pete Lewis and the goat who got £100.”

Yet Ross Smith and his co-writers Tim Dennison and director Jim Groom had succeeded where others had failed. They had actually made a movie in an era it was considered all but impossible without substantial funding. They had created a work of art that would outlive them all, and also made what many regard as the first “wannabe movie.” A film that is finally going to get a “bells and whistles” re-release this year.

As Ross, who is now 62, points out in his book See You at the Premiere: Life at the Arse End of Showbiz, “Revenge of Billy the Kid was possibly the best life experience I’ve ever had. Despite everything, I wouldn’t have missed a second of Billy because it’s only now, only years down the line, that I realise it was way beyond just a movie. Revenge of Billy the Kid, both the film and its production, was a reflection of who I, and everyone who worked on it, was at that time in our lives.

“Billy could only have been the result of people in their twenties. It’s a statement of youth and its attendant self-belief, determination, hope, audacity, arrogance, energy, irreverence, naivety, anarchy, enthusiasm and ambition. In an interview for Billy, given when I was 26 I said I wanted to be a millionaire and win an Oscar before I was 30. I actually said that. It’s in print. I believed those words. Good for me! That’s how everyone in their twenties should be, filled with ludicrous, brazen overconfidence.”

It’s safe to say that without the arrogance of youth, Billy would never have been made.

And the great adventure began one day in 1988, when a group of three friends with backgrounds in the film and TV business decided to get together and do what had never been done before and make a feature film completely off their own backs.

Ross explained, “We wanted to make a low-budget, independent film in an era when what would become known as wannabe films simply didn’t exist. We were only in our twenties but between us we had some experience in the film industry so we weren’t a complete group of chancers who didn’t know what they were doing. We just didn’t have an executive producer or a big budget to play with.”

Ross added, “Jim was a massive Hammer horror fan, and I loved all the Carry On films. So we decided to make a horror with an element of humour. No one was going to see British films at the time, and so we wanted to do our own thing with a sense of fun and a bit of outrage.”

Before asking anyone to put their hands in their pocket and invest, they needed a script, and so the three friends met to brainstorm and in Ross’s words, “ It quickly became apparent that almost every low-budget film is, in production terms, the same: a group of characters are trapped in an isolated location then, literally or metaphorically, chopped up. In addition, we knew locations are intrinsically linked to budget. Locations define your costs for sets, travel and accommodation. So, I proposed we think of one location which came with lots of sets. Tim suggested a hospital.”

After toying with the idea of a story involving an aborted mutant foetus growing big and ferocious on amputated limbs and body organs, until it grows powerful enough to kill the doctors responsible, they decided against the idea because a hospital would be too difficult a location to secure, and the abortion aspect could alienate and offend a large part of their audience.

Returning to the drawing board, they eventually came up with the idea of a farm on an isolated island where “The farmer shags a goat, and the mutant offspring slaughters his family?”

As film pitches go, it’s an unusual one, but it fitted their mission statement to launch a grenade into an industry they saw as ailing and struggling under the weight of “precious, parochial films.”

The next step was to find a farm!

An abandoned and rundown house in the wilds of Gloucestershire seemed perfect until they were told about the story of the mad axeman who used to live there and was due for release in a few weeks.

Their journey eventually led them to the outskirts of Abergavenny.

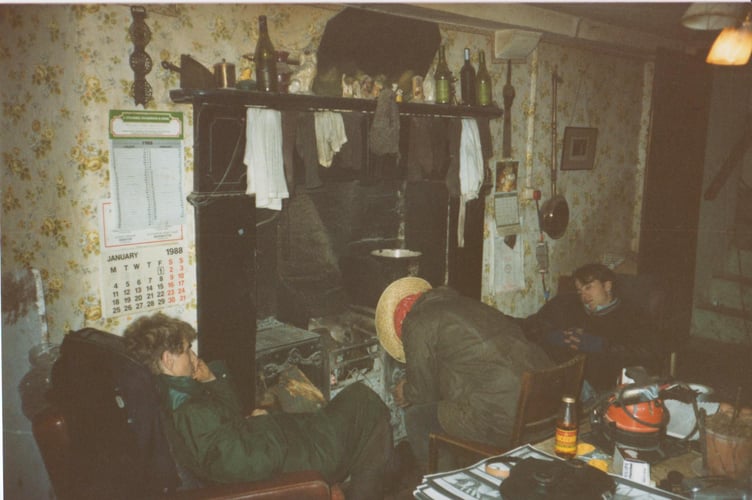

Ross recalled, “We caught sight of what appeared to be a derelict farmhouse. Approaching it, a farmer in his mid-thirties, but who could have passed as a decade older, met us alongside his unleashed Border Collie. The farmer introduced himself as Pete Lewis and his dog as Roy.

“Pete seemed willing to have a film unit take over his life for a month and showed us his two large, run-down barns and 200-year-old farmhouse. Inside, the kitchen floor was partially carpeted with straw. There was no running water, except from a stream outside. Stored alongside groceries were animal feed and various agricultural implements.

“Pete took us from the post-apocalypse beauty of the farmhouse for a tour of his fields, livestock, woodland and stream. I went to the lavatory, a wooden hut perched about fifteen feet above the stream. Inside was a horizontal plank of wood with a hole in it.

“Gazing into the hole, I was confronted by a large mound of s**t and s**t-stained newspapers on the ground below. After my pee, I asked Mr Lewis how I flushed the toilet. He explained that when the storms come, the stream rises and sweeps away the effluence. I asked Mr Lewis when the storms had last come. ‘April’, he replied that November day.

“We had found our farm.”

Reflecting on life on the farm, Ross explained, “We had a great relationship with Pete. He did complain for the first few days because they’d be a 20-man crew in his house up all hours filming, and he said he needed to get some sleep because he had to be up first thing, but he slowly adapted to this brief interlude in his working life and began eating with us and going out of his way to help us out.

“I remember one time we told him we needed some dead rabbits for a certain scene, and could he get us some. He said, ‘No problem’, and the next thing we knew, some almighty bangs was coming from the fields, and Pete was walking back carrying some freshly shot rabbits. We were mortified! When we’d asked him to get us some dead rabbit, we thought he’d go to the butchers, not shoot them himself!”

Filming at the farm was a memorable experience, especially the arrival of the actor Michael Balfour, whose first scene involved casting a lustful glance at a goat.

Ross wrote in the diary he kept while making the film, “Michael surprises me. I had, initially, regarded him as a theatrical luvvie and was worried he was miscast as Farmer Gyles. I was so wrong. From the moment Jim calls ‘Action’ Michael becomes Gyles MacDonald. He’s grotesque, funny, superb. Michael has no vanity or ego. He doesn’t care if he gets dirty or appears gross, he just gets stuck into the part of Gyles and seems to be having tremendous fun. Equally remarkable is the instantaneous transformation from coarse, vulgar, impetuous goat-shagger back to refined, intelligent, easy-going actor.”

After the scenes in Abergavenny were shot, it was still a long road to an eventual release, and although the film pretty much dropped off the radar in most quarters, it has gone on to become something of a cult classic.

Ross told the Chronicle, “There have been many occasions over the years when I’ve had surprise encounters with people who had not only seen but loved the film. For brevity’s sake, I’ll just tell you about the one a few years ago when I was in a bar in the West End with a group of friends talking about bizarre films.

“Anyhow, I went to get a drink and got talking to the barman about the same topic, and he said to me, ‘Talking about bizarre films, there was one in particular called ‘Revenge of Billy The Kid’ that me and my friends used to bunk off School to watch.’

“I said, ‘You’re looking at one of the guys who wrote it.’

He replied, ‘Bullsh*t!’ But I managed to convince him and then he shouted to the rest of the pub, ‘Over here! This is the guy who co-wrote ‘The Revenge of Billy the Kid!’’

“I was expecting a standing ovation,” laughs Ross, but I just got a few curious looks and people carried on with what they were doing.

“Yet, regardless of whether you’ve heard of it or not, that film will outlive us all, and that makes all the sweat, blood, tears, and criticism worthwhile.”

Ross elaborated, “Because whether it’s hated or loved, the important thing is to get a film over the line to show people you’ve got the drive and discipline to deliver the goods.

“I can’t stress enough that you need to deliver projects. No one with the clout to further your ambitions will have confidence in your abilities if you don’t deliver, if you don’t show them what you can do. That’s the best advice a creative person can ever receive.

“Stop talking about things you’re going to do – no one cares so long as all you do is talk – and deliver. Deliver something onto that page, that screen, that stage, that music file. Because every hour you make excuses for not delivering, is another hour when someone else is delivering.

“Everything you say you’re going to deliver is bullsh*t. It really is. It’s bullsh*t. Everyone in the film industry, everyone across the arts, knows you’re talking bullsh*t, even though they don’t tell you to your face, until you deliver. So, shut up and…deliver!”

Even Billy the Kid himself couldn’t have said it better!

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.