WE all take clean drinking and bathing water on tap for granted. Almost as if it were our birthright. Yet rewind a few generations, and you could too have been drinking from a contaminated well or showering in a bucket of stale slop.

Alongside electricity and Netflix, sanitation is one of the marvels of the modern age.

Just imagine what the foul-smelling and grime-encrusted folk of yesteryear would have made of our hot baths, steaming showers, and crystal clear drinking water that flows like a fountain from the Garden of Eden.

Not to mention the bountiful supply of clean water that powers our washing machines to leave our clothes as fragrant as a summer rose.

And then there’s the dishwashers, which use excessive amounts of the wet stuff to effortlessly scrub our dishes cleaner than a horde of unruly and surly servants ever could.

We are living in marvellous times indeed!

Yet it wasn’t always this way.

Less than two hundred years ago, leafy Abergavenny was literally swimming in filth. Large sections of the town were something akin to an open sewer. A terrible combination of blood and sewerage ran through the town like the forewarning of some apocalyptic happening.

People were drinking from poisoned springs, washing their clothes in dirty rivers, and dreaming of the day when the first bottle of bubble bath would be invented.

Something had to be done!

And it was!

A reservoir was built.

The end!

….Yet that’s not quite the full story.

Rewind the clock to 1793, and a gang called the Improvement Commissioners descended on Abergavenny like a flock of benevolent crows to find out ways they could improve things for us.

Much to their satisfaction, it was noted that, courtesy of the Reverend John Williams, there was already a small reservoir in existence.

However, the lead pipes that ran from the Pond Head to Abergavenny were made of lead and in dire need of repair.

There was much discussion about a new pipe system that would be made of elm, but this didn’t take place until 1805, when over 44 tons of elm were purchased from a lady named Mrs Kinsey.

Eight years later, and 820 yards of iron mains were ordered from Blaenavon and dutifully laid.

Nevertheless, in those heady days of innovation, enterprise, and repugnant odours at every turn, the water pressure was painfully slow, and the supply was often polluted.

A case in point was an invoice sent to the Improvement Commissioners in 1829 by one Thomas Newman, who had the unpleasant job of removing a dead ass from the reservoir.

The general consensus was that, in terms of sanitation, things weren’t moving with the momentum they should have, and the promised utopia wouldn’t build itself. Instead, low-paid labourers would.

An 1860 Act of Parliament gave the Commissioners the power to erect a new waterworks. Game on!

Intoxicated with the thought of all that was foul and filthy about Aber being cleansed in a torrent of pumped, primed and pure water, John White wrote, “By virtue of this act… a bountiful supply of water of great purity was obtained from St Teilo’s Well at Llwyndu. Within the past two years, other springs have been discovered, yielding a larger additional supply of water, which has been diverted into the covered reservoir at St Teilo’s Well. The height of the well above the general level of the town is about four hundred feet. The water is conveyed by pipes direct from the reservoir to the town, the supply being so abundant even in the driest seasons, that the pipes are nearly always full; and owing to the elevation from which the water proceeds, so great is the pressure, that in the case of fire, engines are not needed.”

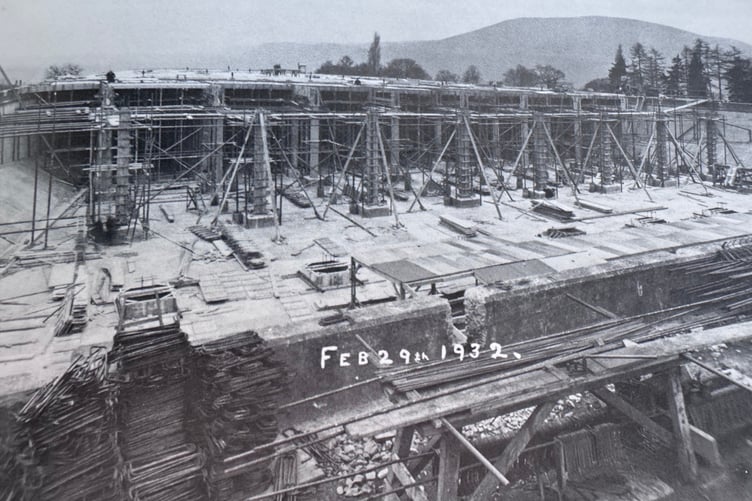

For awhile, all was fair and good in the garden of Abergavenny, but as time ticked on, the town was prospering, population was booming, and demand had far outstripped supply. A second, much larger reservoir was built in the same location and in 1932, it was decided to cover it with concrete.

The Abergavenny Chronicle of April 15 explained, “It is hoped that the scheme for covering will forever solve Abergavenny’s water troubles. There is no purer water in the country than that which comes from the Llwyndu and Sugar Loaf springs, but it is well known… that the underground spring water must not be exposed to the sun’s rays before it reaches the consumer.

“It is in open storage that diatoms develop, which, while not really harmful, are unpalatable and unpleasant and cause the consumer to anathematise the water committee.

“Experiments with chlorinating plants were partly successful in that the fearsome-sounding amphipleura pelludica was eliminated, but still the growth of diatoms continued and affected the pristine purity of the water.

“There were two alternatives: a filtration plant, or covering the reservoir. Financial considerations decided the council in favour of covering the reservoir, for a filtration scheme would not only involve a large capital expenditure but future expense of maintenance.”

Unfortunately, work on the covering of the reservoir did not go smoothly.

The Chronicle recorded there was an incident where the scaffolding poles broke,and three men fell 24 feet to the floor of the reservoir.

David Jones of Walter Street, Tredegar, and George Hill of Glyn Terrace, Tredegar, suffered only bruising and shock, but William Henry Llewellyn of White House, Llwyndu, died from his injuries at the Cottage Hospital later that day.

The Chronicle reported, “At the inquest, it was found that there were two nail holes and a knot at the point where the scaffolding pole broke. Daniel Gethin of 3, Greenfield Cottages, Lower Monk Street, who had eight years of experience erecting scaffolding, tested the scaffolding poles before erecting them by leaning them against something and jumping on them. He agreed with the Coroner that if he had seen the two nail holes in the wood, he would not have used the pole. The Coroner did not think that there was any negligence on the part of the contractors, so the verdict was “death by misadventure.”

A small civic occasion marked the opening of the newly covered reservoir, and before the Mayor, Councillor A.E. Tillman turned on the water with what he termed “the golden key,” Alderman Rosser, the chairman of the Sanitary and Water Committee, had a few choice words to say.

“I am going to ask the Mayor to turn on the water for the benefit of posterity. Posterity has never done anything for him, but he is going to do something for posterity,” he explained to much laughter and applause.

After wrestling gamely with the stop-cock, the Mayor finally turned the taps on, and the water flowed.

Or at least it did, until Grwyne Fawr and Talybont Reservoir took its place.

There have been leaks on social media that since Llwyndu Reservoir was decommissioned and the torrents of spring water diverted into the Cibi, Abergavenny has been subjected to routine flooding, but that’s a story for another day…..

In the meantime, pour yourself a cool glass of water, run a hot bath and raise a toast to the wonder that is effective sanitation!

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.