‘WHEN my Dad bought our farm he failed to take notice of a working quarry, no more than a few yards from our boundary. It was Penlan quarry where the famous blue stone was quarried.

‘Our first introduction to this was early in the morning when a very loud whistle was blown followed by the loudest bang we had ever heard. Then we were bombarded by UFO’s, large and small, as stones became airborne, some landing in the yard, even on our roof.

‘This went on at least twice a day for the next sixteen years. You put your life in your hands at those times.’

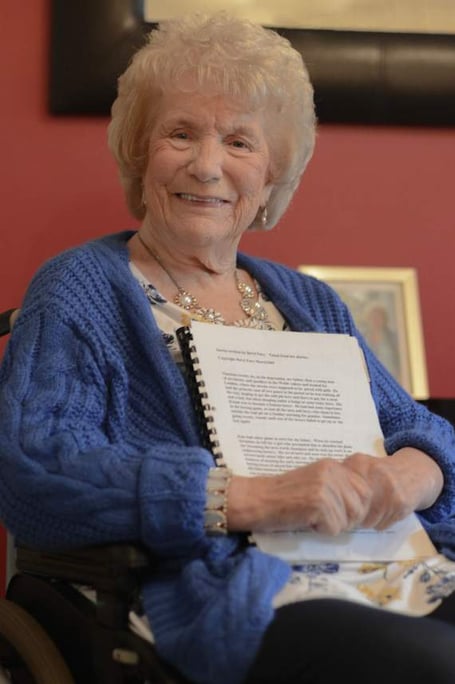

Beryl Fury of Mardy, Abergavenny, is now 84, but her memories of life in rural Monmouthshire in the first half of the twentieth century are as vivid as ever.

She has collected them together in a fascinating and eye-opening memoir which she hopes to publish in book form in the near future. The entertaining and often hilarious tale is populated by characters who passed through her world in times very different to our own.

Beryl, author and poet, was one of eight children brought up on the farm with no electricity or running water - but it is the happiness and love of family and the free spirit of youth that shines through in her writing.

She recalls, ‘In the long winter months, when the cows never left the shed,the heat from their bodies would rise up and become my central heating. Their munching or chewing the cud and the occasional bellow was my background music and the smell was my perfume.’

It was, however, relentlessly hard; treats were few and every penny had to be wrung from the unforgiving land. Not for Beryl the luxury of pets, although she did adopt a litter of fox cubs and suffer her father’s wrath after bringing them into the farmyard.

Beryl remembers, ‘I sat down in the yard and started crying bitterly, the foxes climbing all over me in their quest for breakfast. ’I cannot believe she’d do this,’ my father was saying, ’Bringing foxes into a yard full of chickens. Where is your sense child? They cannot stay here.’

Sometimes the animals would strike back, like Oscar the Cockerel who terrorised the family and anyone foolhardy enough to visit. however, when Father had finally had enough of him, Beryl remembers lamenting his passing.

‘We breathed a sigh of relief the day dad wrung his neck, but when Mum dished him up for dinner, us children took one look and none of us would eat him. Looking at him nestling on the meat dish, with a crown of roast potatoes around him, my Dad said, ’Brenda, that was a good bird and an excellent yard watch dog.’ Mum had to agree.

Beryl recalls trips to Abergavenny Market during school holidays when, she says, ‘Dad and Mam would leave the eight of us in the Park by the Bandstand while they went off to market to do what they had to do. We would play happily there all day long until they came to pick us up.’

Having few luxuries, it was a bone of contention to Beryl when a better-off relative came to stay, resplendent in his fine red wellingtons. Beryl asked to try them on but was rudely rebuffed and so she plotted her revenge.

‘That evening when we sat down to tea, David’s wellies were in the porch and I went to bed thinking of them. Next morning I was up early, just to try on the wellies. They looked good on me, better than on him.

‘If I could not have them I`d make sure he did not have them to wear either. Making sure no one was watching, I grabbed them and hurried out, on the mountain, to the rushing stream we had visited yesterday. I filled the wellies with water and watched them sink. That had put paid to them and his showing off, I thought.’

As an adult, Beryl was equally forthright when faced with injustice. During the Miners’ Strike, Beryl was raising funds for strikers and their families in Abertillery when the manager of a large store told her to leave his premises.

‘I had a ferret on a lead and told him if he didn’t make a contribution to the cause the ferret might accidentally escape and run around in his shop. He paid up and we left.’

Tragedy struck for Beryl on the eve of a long-awaited holiday back in 2015. She recalls, ‘We were travelling to Bristol Airport and my head felt a bit funny, not a pain as such - but just odd. I collapsed in the airport and passed out. As I was coming around I heard someone shouting, ‘My God, she’s had a stroke!’ I remember clearly thinking, ‘Some poor bugger’s in trouble’, not realising it was me.

Beryl lost much of her mobility as a result of her stroke and says she now has difficulty remembering things. ‘It is important that I write all these memories down so they can be kept for those to come. It would be a shame if they were all lost,’ she says.

She also managed to pack into her life a spell as a serving soldier with the WRAC which, she says, was hard work but a career her early life had prepared her for.

Not one to rest on her laurels, Beryl is now looking for ways to get her memoir into print and, with the sales it deserves, there might even be another tale to tell. As she says , ‘Life is for living, you’re a long time dead.’

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.