THE Monmouthshire Merlin newspaper of the 29th of January 1848 opened with the following paragraph: “For some weeks various surmises have been afloat respecting the death of a small farmer named William Howells, who lived near Llanellen, Abergavenny, and as subsequently to his burial the wife of the deceased has conducted herself in a manner which excited suspicions, various persons living in the locality, knowing that Mr. Howells died without being attended by any medical person, were not slow in charging his wife with the cause of his death.”

The coroner, Thomas Hughes, became aware of what was being said and considered it necessary to hold an inquest. Mr. Howells’s body was subsequently exhumed eight weeks after the burial in St Helen’s Church graveyard, Llanellen.

A jury met with the coroner at the Hanbury Arms in Llanellen on Friday the 7th of January and Mr. Steele, a surgeon of Blaenavon, was given the body to carry out a post mortem examination. The inquest resumed one week later at the George Hotel in Abergavenny where Mr. Steele confirmed that a large quantity of arsenic had been found in Mr. Howell’s body and this was the cause of his death on the 10th of November 1847.

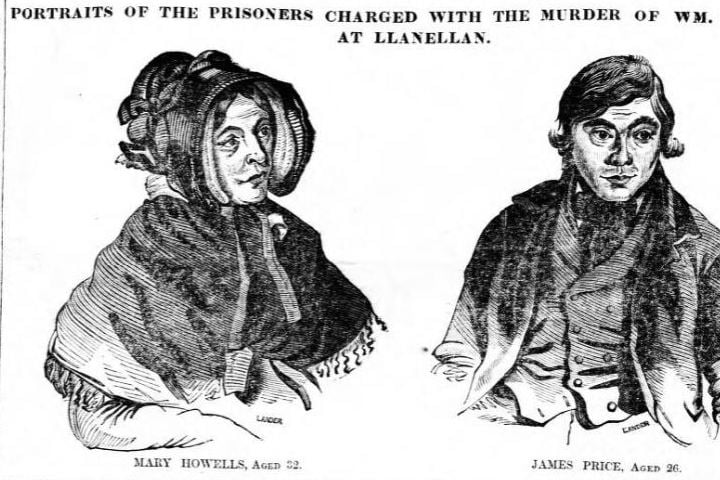

A Grand Jury was summoned on Monday the 27th of March 1848 where the findings of the inquest jury were outlined to see if they thought a charge of wilful murder could be brought against Mary Howells, widow of the deceased, and James Price who was a servant on the farm. Testimony from the surgeon stated that arsenic was the cause of death and therefore the question that needed to be answered was: “Did the accused have any part in administering that poison?”

Consideration must also be given to evidence that Mary Howells and James Price have been living together in a rather unbecoming and improper manner since the death of William Howells from which may be concluded that there is an obvious motive for the commission of a crime. Furthermore, there is evidence that James Price tried to throw the blame onto a servant girl, Jane Morgan, (who lived in the house at the time) as he had gone to the girl’s room with a witness and deliberately picked up a gown and shook it from which a small paper packet fell to the floor.

The packet contained a white powder which appeared to be poison and the obvious inference is that it had been planted there by the accused. The Grand Jury came to the conclusion that there was a case of wilful murder to answer and the trial of Mary Howells and James Price was scheduled for the following day.

The court was packed with local people who were curious to see the accused standing in the dock. Mary Howells was dressed all in black and appeared to have a respectable appearance. James Price was also dressed in black but neither prisoner seemed unduly concerned about the forthcoming trial. The jury of twelve men took an hour to be selected. The prosecution opened the proceedings by stating that the evidence in this case, as in similar cases, would be principally of a circumstantial nature.

The first witness, James Powell, stated that he had originally been involved with the burial of William Howells on the 13th of November last and he confirmed that it was the same body that had been exhumed on the 7th of January. Richard Steele, a surgeon of Blaenavon, gave a very detailed account of the post mortem that he carried out and he concluded that arsenic had been the cause of death.

A neighbour by the name of Mary James said that the accused, James Price, had come to fetch her on the morning of William Howell’s death saying that his master was very ill. She stated that Mrs. Howells was being very attentive to her husband who was in great pain. They discussed at length how they could alleviate William’s obvious distress with traditional home-made remedies. Mrs. Howells had mentioned several times that she had sent for a doctor but the witness said that she had not seen any sign of a doctor all the time she was in the house.

Another neighbour, Catharine Williams, gave evidence to say that she had known Mr. and Mrs. Howells since their marriage about eight years ago. She had called on the couple on the day that William had been taken ill and discussed with Mrs. Howells the best way to treat her husband’s condition. She called back later and William died while she was there and she helped to lay out the body. She then said that three weeks later she talked with Mrs. Howells about raising her husband’s body but she was not willing for that to be done. But when the matter was discussed again Mrs. Howells said she had no objection to his being raised.

The servant girl, Jane Morgan, spoke at length about her duties in the house which mostly involved preparing meals for everyone. The prosecution was trying to work out if there were any irregularities in the meal preparations that may have singled out some food that could have contained the poison and been deliberately given to Mr. Howells. She had moved out after his death but had left a gown in one of the upstairs rooms and later heard that some powder had been found in it but she denied any knowledge of this. Jane said that her life was comfortable in the Howells household and her master had been good to her at all times.

The next witness was Edward Evans, a druggist from Abergavenny, who said that he had known Mary Howells for about six years and he remembered selling her a pennyworth of arsenic last September. When questioned he admitted that arsenic was commonly used to treat certain conditions in sheep.

John Howells, a brother of the deceased, said he had talked to James Price and asked him why they had not sent for a doctor when Mr. Howells was ill. Price replied that there was no time to do so.

Another brother of the deceased, Howell Howells, said he asked Mrs. Howells why a doctor had not been sent for. Her answer was that there were only three of them in the house and we could not leave her husband. It was noted that neither brother had been invited to the farm for tea after they had attended the funeral.

The curate of Llanellen, the Reverend William Jones, was next in the witness box. He said he had met James Price the night before Mr. Howells died and on hearing about his illness, told Price to tell his mistress to send for Mr. Steele, the surgeon from Blaenavon. He then met Mrs. Howells on the day after her husband had died and remonstrated with her for her imprudence in not sending for a doctor. She seemed sorry she had not done so and said her husband would not allow her.

Then he said: “I recollect the inquest being held on the 18th of January 1848. Mrs. Howells brought me a paper of white powder, requesting me to keep it in my possession until the 21st, the day of the adjourned inquest. On the 21st, I saw Mrs. Howells at Mr. Lewis’, the iron monger of Abergavenny, and, on talking to her about the packet, I said I was apprehensive that would lead to the conviction of the guilty parties. She said she hoped it would. I said I hoped it would not return upon her own head; she said she was not afraid of that. When she brought me the parcel, she said the boys were preparing to go to Abergavenny, and they went upstairs to change their clothes, and in searching for a handkerchief, the packet fell out of the girl’s gown. By ‘the boys’, I understood her to mean Thomas Davies and James Price.”

He then went on to say that the prisoner and her husband were persons in whom I took a considerable interest. There had been disagreements between them in the past, because he had a jealous nature, but they had lived happily together for the last 12 months. I always found James Price a decent young man in his behaviour.

The registrar of births and deaths at Abergavenny, John Davies, was next to give evidence. He said that James Price had come to him to register the death of William Howells. Price said the cause of death was cramp in the stomach and I asked him for a medical certificate; he said he didn’t have one. I asked why a doctor had not been sent for; he said his master would not have one. I told him I could not give a certificate and that he must go to the coroner as I thought it was a case for him. I also said I thought all was not right, but that if the coroner would not hold an inquest, I would give him a certificate.

Next in the witness box was Thomas Davies, a friend of James Price, and he said he had gone to live with Mrs. Howells after her husband’s death. He related the story about finding the white powder in a gown belonging to the servant girl, Jane Morgan. James Price had asked him to shake the gown and he had done so to no effect. Price told him to shake it again but nothing happened but on shaking the gown for a third time, a parcel fell out. Price called Mrs. Howells up to the room and asked her what she thought the parcel was. She opened it and said “here’s the poison”. Price then said “I warrant it was the girl that gave it to him”.

Patrick Cusack, a police superintendent from Abergavenny, said he had searched the house of Mrs. Howells after her husband’s death but found nothing of poison there. It was near the end of the inquest that Mary Howells was taken into custody. Whilst in custody James Price started talking to his jailer, John Royston, and said that you are keeping the innocent ones in here but you have left the guilty one, Jane Morgan, go free. He said the poison was given to Mr. Howells by the servant girl. This closed the case for the prosecution and it had lasted 9 hours.

Mr. Cooke, counsel for the defence, then addressed the jury on behalf of Mrs. Howells and outlined the following possible scenario. It is a fact that Mr. Howells had died from the effects of arsenic but the poison was administered by accident. Mr. Howells had been preparing a solution of arsenic to treat scabies in his sheep. Some of the liquid had been left in a jug on the supper table. When he asked for a drink of milk and water, the servant girl, Jane Morgan, had put the milk and water in the jug and thereby unintentionally administered the poison to her master, thus causing his death.

He also spoke at length on behalf of James Price and claimed that the prosecution had failed to show how the poisoning had occurred. As the time was now 9:30 in the evening the judge deferred the summing up until the following day. As the trial resumed, the judge started by saying that this was a very important and serious case; but one, nevertheless, the proof of which depended entirely on circumstantial evidence. Death was caused by arsenic poisoning but the jury had to decide whether the poison had been administered wilfully or accidentally. He also pointed out that the jury must pay particular attention to all the verbal evidence given during the trial. The summing up lasted for one and a half hours and seemed to be biased towards the prosecution not proving the case.

The Berrow’s Worcester Journal of the 6th of April summarised it as follows: “The trial occupied two days, and Mr. Justice Patterson, in summing up the lengthy circumstantial evidence, said it was clear the deceased died from poison, and he minutely pointed out every fact, as it weighed for or against the prisoners. His Lordship was thus occupied for nearly two hours, and the inclination of his reasoning on the whole case was decidedly in favour of the prisoners”.

The jury then retired but were recalled back into court a few minutes later. The judge said he had an important fact that the jury should be aware of. Mr Howells was then sworn in and he stated that he had met with Mrs. Howells on the day after her husband’s death and said that he thought an inquest was necessary and she agreed that he should go and inform the coroner. He then met with the coroner but no inquest was held.

The coroner, Mr. Hughes, then took the stand and confirmed that he had talked with Mr. Howells but he did not think an inquest was necessary. He asked Mr. Howells to speak with the clergyman of the parish and if any more came out, to let him know. He had heard nothing more on the matter. The jury then retired, and after a short absence, came back into the court, and in an interval of almost breathless silence, delivered a verdict of “NOT GUILTY”!

The crowded courtroom became very excited and had to be suppressed by officers of the court and the two accused quickly left the room.

The last word has to go to the vicar of Llanellen church. He added the following words to the burial register for William Howells: “supposed to have been poisoned”.

-was-inducted-for-the-Athletic-Achievement-Award-and-Bill-Owen-MBE-(right)-earned-h.jpeg?width=209&height=140&crop=209:145,smart&quality=75)

.jpeg?width=209&height=140&crop=209:145,smart&quality=75)

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.